GQA: “What is the Evidence for Jesus’ Death and Resurrection?”

“What is the Evidence for Jesus

Death and Resurrection?"

By Scott Wakefield

Death and Resurrection?"

By Scott Wakefield

Prompted by conversations with parents concerned about their children having declared personal allegiance to an alternative to Christianity and because I increasingly sense the need to provide credible evidence for deep Christian faith, I wanted to give an overview of the evidence for the physical death and resurrection of Jesus.

Nota Bene:

Nota Bene:

- Because the death of Jesus is far less controversial and a more settled matter than His resurrection, resurrection eventually becomes the main focus of argumentation.

- Links to citations in footnotes (which are active in the PDF, downloadable at fccgreene.org/resurrectionbooklet) have been shortened to save space but nonetheless are each referring to specific locations that may not be immediately recognizable, e.g., “crossway.org” is used multiple times but will all go to different locations. So just because the footnote link looks like it’s the same one already cited, it’s likely not.

Why This Matters

All truth—everything real—is grounded in time and space, in history. Otherwise, it remains mere theory. It might entertain as sci-fi, but it categorically fails as a foundation for one’s life.

If the Christian faith is true, it must be rooted in verifiable history. Nowhere is this more important than with the resurrection. As Paul says in 1 Corinthians 15:19-20, “if in Christ we have hope in this life only” and He has not been raised, “we are of all people most to be pitied.” But if He has been raised, then the resurrection is a linchpin of reality—it verifies supernatural power, confirms divine revelation, and demands our trust.

Theologian Geerhardus Vos puts it this way: “[T]he process of revelation is not only concomitant with history, but it becomes incarnate in history. The facts of history themselves acquire a revealing significance.”1 God’s acts are not myths or abstractions—they are personal revelations. When God acts in history, He is revealing Himself: a holy God breaking into an unholy world to make Himself known.

Because Christian faith hinges on whether a supernatural God did or did not reveal Himself in history, this article provides an overview of the evidence for Jesus’ death and resurrection in four categories—biblical testimony, extrabiblical history, modern scholarship, and sociological attestation.

If the Christian faith is true, it must be rooted in verifiable history. Nowhere is this more important than with the resurrection. As Paul says in 1 Corinthians 15:19-20, “if in Christ we have hope in this life only” and He has not been raised, “we are of all people most to be pitied.” But if He has been raised, then the resurrection is a linchpin of reality—it verifies supernatural power, confirms divine revelation, and demands our trust.

Theologian Geerhardus Vos puts it this way: “[T]he process of revelation is not only concomitant with history, but it becomes incarnate in history. The facts of history themselves acquire a revealing significance.”1 God’s acts are not myths or abstractions—they are personal revelations. When God acts in history, He is revealing Himself: a holy God breaking into an unholy world to make Himself known.

Because Christian faith hinges on whether a supernatural God did or did not reveal Himself in history, this article provides an overview of the evidence for Jesus’ death and resurrection in four categories—biblical testimony, extrabiblical history, modern scholarship, and sociological attestation.

Biblical Testimony

The New Testament as History

It is critically important to recognize that the New Testament record itself functions as primary source material in the same way other ancient historical sources do.2 The Gospels and Acts are written in the recognized literary genre of Greco‑Roman biography and therefore must be scrutinized as extrabiblical historiography. They are archaeologically bona fide—anchored to real people (Pontius Pilate, Herod Antipas, Caiaphas) and verifiable places (Jerusalem, Galilee, the Praetorium). Their authors either were eyewitnesses or drew directly on eyewitness testimony, and the bulk of the material—all four Gospels, Acts, and Paul’s major letters—was in circulation within one human generation of the events it records, remarkably recent compared to most ancient accounts.3 Luke expressly states that his purpose in writing was to compile an orderly, researched account so that readers could “have certainty concerning the things you have been taught” (Luke 1:1‑4). Paul invites verification when he reminds the Corinthians that most of the five hundred witnesses to the risen Jesus were “still alive” (1 Corinthians 15:6). Modern historians—believers and unbelievers alike—treat the New Testament, not as legend spun centuries later, but as a collection of early, multiple, and independent sources—as history. Any credible inquiry into the death and resurrection of Jesus must allow the New Testament itself to count as first‑century historical data. Because these same tests are used on Caesar, Alexander, or the diaries of Lewis & Clark, treating the Bible by identical standards is not special pleading—it is simply doing responsible history.

Gospel Accounts (Crucifixion and Resurrection)

All four canonical Gospels provide compelling, historically credible, and mutually reinforcing eyewitness testimonies to Jesus’ literal death by crucifixion and His physical, bodily resurrection—recording them with the simple clarity of historical fact rather than mythological embellishment. Matthew records the supernatural darkness, earthquake, and temple veil being torn as Jesus died (Matthew 27:45-54), followed by guards being posted at the sealed tomb yet still finding it empty on the third day. Mark, considered the earliest Gospel, emphasizes the historical reality with precise details like “the third hour” of crucifixion and Jesus’ loud cry before death (Mark 15:25, 37), concluding with women discovering the empty tomb and an angelic announcement: “He has risen! He is not here” (Mark 16:6). Luke adds unique details of Jesus’ physical post-resurrection appearances—eating broiled fish (Luke 24:42-43) and inviting the disciples to “touch me and see” his flesh and bones (Luke 24:39)—directly countering any notion that the resurrection was merely spiritual. John’s account provides the testimony of the disciple “who saw it” (John 19:35), recording precise burial details (75 pounds of burial spices) and the discovery of abandoned grave clothes still lying in their wrapped position (John 20:6-7), indicating neither grave robbery nor spiritual visions.

The singular message—agreed upon by all four Gospels—involves all 13 following details: During Passover in Jerusalem, Jesus of Nazareth was tried by the Roman prefect Pontius Pilate, crucified at Golgotha between two others with the charge “King of the Jews” posted above Him, offered sour wine while soldiers cast lots for His garments, and watched by a group of women led by Mary Magdalene; when He died, Joseph of Arimathea wrapped the body in linen and laid it in a rock‑hewn tomb sealed with a great stone before sunset. At dawn on the first day of the week those same women found the stone rolled away, the tomb empty, and heard angelic testimony that Jesus had risen; they became the first witnesses of His bodily resurrection, which He confirmed later that day by appearing alive to His gathered disciples.4 These four independent testimonies provide multiple attestation—while complementary in their core facts, they contain distinct perspectives and details that establish the historical authenticity of Jesus’ death by Roman crucifixion and His bodily resurrection, all recorded as naturally as other events they chronicle.

Paul’s Testimony and Early Creed

The credibility of Paul’s testimony is strengthened because of its historical proximity to Jesus’ death and resurrection. Paul’s letters, mostly written roughly 20–30 years after Jesus’ death—relatively recent compared to much ancient historiography5—affirm both the crucifixion and resurrection as central to the Christian message. In 1 Corinthians 15:3-8, Paul passes on an early creed he received, stating: “Christ died for our sins in accordance with the Scriptures… he was buried… he was raised on the third day … and he appeared to Cephas (Peter), then to the Twelve. Then he appeared to more than five hundred brothers and sisters at one time… then he appeared to James… and last of all… he appeared to me.” This creed is widely recognized by scholars as pre-Pauline material dating to within 3-5 years of the crucifixion, making it the earliest documentary evidence we possess. Its formulaic language, non-Pauline vocabulary, and Semitic thought patterns reveal its origin in the Jerusalem church. When Paul writes “I delivered to you... what I also received” (1 Corinthians 15:3), he is deliberately using technical rabbinic terminology for the formal transmission of sacred tradition. Furthermore, Paul explicitly confirms he “received” this confession directly from eyewitnesses during his visit to Jerusalem three years after his conversion (Galatians 1:18-19), where he spent fifteen days with Peter and met James, the Lord’s brother—both named as resurrection witnesses in the creed itself. His letters (e.g., Romans 6:4, Philippians 2:8-11) repeatedly refer to Jesus’ death and resurrection, showing that these events were established fundamentals of Christian belief from the beginning. This carefully preserved early confession, combined with Paul’s personal transformation from persecutor to apostle, provides compelling first-generation evidence that Jesus’ followers genuinely believed they had encountered a resurrected Christ.

Other New Testament Writings

Given the diversity of authors, cultural settings, recipients, and genres outside the Gospels and Paul’s writings,6 the rest of the New Testament provides a remarkably consistent witness to Jesus’ death and resurrection. Throughout Acts, the proclamation of the resurrection forms the non-negotiable core of apostolic preaching, with the disciples consistently emphasizing their direct eyewitness testimony that God raised Jesus from the dead (Acts 2:23-24, 32; 3:15; 4:10; 5:30; 10:40; 13:30-37; 17:31). The epistle to the Hebrews describes Jesus as the one who “endured the cross,” “is seated at the right hand of the throne of God” (Hebrews 12:2), and was “brought again from the dead” (Hebrews 13:20). Peter’s epistles speak of the resurrection as the basis of Christian hope (1 Peter 1:3, 21).7 James, the Lord’s brother (named by Paul as a resurrection witness), alludes to “the Lord of glory” (James 2:1)8. John’s first epistle grounds assurance in the present, embodied Son—“that which we have seen with our eyes … and touched with our hands” (1 John 1:1-2); 2 John warns against deceivers who refuse to confess “Jesus Christ coming in the flesh” (v 7); and 3 John praises missionaries who travel “for the sake of the Name” (v 7). Each line assumes that Jesus is not a past ideal but a still-incarnate, bodily risen Lord.9 In Revelation the risen Jesus proclaims, “I died, and behold I am alive forevermore” (Revelation 1:18), a declaration echoed throughout the book, which presents Him as the slain-yet-living One who has conquered death and now reigns forever.10

Taken together, every layer of the New Testament—Gospel narratives, Paul’s letters, sermons in Acts, and later epistles, which were written and circulated within living memory of the events—bears witness to two inseparable events: Jesus’ actual death by crucifixion and His victorious resurrection. These texts were written and circulated within living memory of the events, and they show a consistent testimony of eyewitnesses and early disciples that Jesus truly died and was raised.

It is critically important to recognize that the New Testament record itself functions as primary source material in the same way other ancient historical sources do.2 The Gospels and Acts are written in the recognized literary genre of Greco‑Roman biography and therefore must be scrutinized as extrabiblical historiography. They are archaeologically bona fide—anchored to real people (Pontius Pilate, Herod Antipas, Caiaphas) and verifiable places (Jerusalem, Galilee, the Praetorium). Their authors either were eyewitnesses or drew directly on eyewitness testimony, and the bulk of the material—all four Gospels, Acts, and Paul’s major letters—was in circulation within one human generation of the events it records, remarkably recent compared to most ancient accounts.3 Luke expressly states that his purpose in writing was to compile an orderly, researched account so that readers could “have certainty concerning the things you have been taught” (Luke 1:1‑4). Paul invites verification when he reminds the Corinthians that most of the five hundred witnesses to the risen Jesus were “still alive” (1 Corinthians 15:6). Modern historians—believers and unbelievers alike—treat the New Testament, not as legend spun centuries later, but as a collection of early, multiple, and independent sources—as history. Any credible inquiry into the death and resurrection of Jesus must allow the New Testament itself to count as first‑century historical data. Because these same tests are used on Caesar, Alexander, or the diaries of Lewis & Clark, treating the Bible by identical standards is not special pleading—it is simply doing responsible history.

Gospel Accounts (Crucifixion and Resurrection)

All four canonical Gospels provide compelling, historically credible, and mutually reinforcing eyewitness testimonies to Jesus’ literal death by crucifixion and His physical, bodily resurrection—recording them with the simple clarity of historical fact rather than mythological embellishment. Matthew records the supernatural darkness, earthquake, and temple veil being torn as Jesus died (Matthew 27:45-54), followed by guards being posted at the sealed tomb yet still finding it empty on the third day. Mark, considered the earliest Gospel, emphasizes the historical reality with precise details like “the third hour” of crucifixion and Jesus’ loud cry before death (Mark 15:25, 37), concluding with women discovering the empty tomb and an angelic announcement: “He has risen! He is not here” (Mark 16:6). Luke adds unique details of Jesus’ physical post-resurrection appearances—eating broiled fish (Luke 24:42-43) and inviting the disciples to “touch me and see” his flesh and bones (Luke 24:39)—directly countering any notion that the resurrection was merely spiritual. John’s account provides the testimony of the disciple “who saw it” (John 19:35), recording precise burial details (75 pounds of burial spices) and the discovery of abandoned grave clothes still lying in their wrapped position (John 20:6-7), indicating neither grave robbery nor spiritual visions.

The singular message—agreed upon by all four Gospels—involves all 13 following details: During Passover in Jerusalem, Jesus of Nazareth was tried by the Roman prefect Pontius Pilate, crucified at Golgotha between two others with the charge “King of the Jews” posted above Him, offered sour wine while soldiers cast lots for His garments, and watched by a group of women led by Mary Magdalene; when He died, Joseph of Arimathea wrapped the body in linen and laid it in a rock‑hewn tomb sealed with a great stone before sunset. At dawn on the first day of the week those same women found the stone rolled away, the tomb empty, and heard angelic testimony that Jesus had risen; they became the first witnesses of His bodily resurrection, which He confirmed later that day by appearing alive to His gathered disciples.4 These four independent testimonies provide multiple attestation—while complementary in their core facts, they contain distinct perspectives and details that establish the historical authenticity of Jesus’ death by Roman crucifixion and His bodily resurrection, all recorded as naturally as other events they chronicle.

Paul’s Testimony and Early Creed

The credibility of Paul’s testimony is strengthened because of its historical proximity to Jesus’ death and resurrection. Paul’s letters, mostly written roughly 20–30 years after Jesus’ death—relatively recent compared to much ancient historiography5—affirm both the crucifixion and resurrection as central to the Christian message. In 1 Corinthians 15:3-8, Paul passes on an early creed he received, stating: “Christ died for our sins in accordance with the Scriptures… he was buried… he was raised on the third day … and he appeared to Cephas (Peter), then to the Twelve. Then he appeared to more than five hundred brothers and sisters at one time… then he appeared to James… and last of all… he appeared to me.” This creed is widely recognized by scholars as pre-Pauline material dating to within 3-5 years of the crucifixion, making it the earliest documentary evidence we possess. Its formulaic language, non-Pauline vocabulary, and Semitic thought patterns reveal its origin in the Jerusalem church. When Paul writes “I delivered to you... what I also received” (1 Corinthians 15:3), he is deliberately using technical rabbinic terminology for the formal transmission of sacred tradition. Furthermore, Paul explicitly confirms he “received” this confession directly from eyewitnesses during his visit to Jerusalem three years after his conversion (Galatians 1:18-19), where he spent fifteen days with Peter and met James, the Lord’s brother—both named as resurrection witnesses in the creed itself. His letters (e.g., Romans 6:4, Philippians 2:8-11) repeatedly refer to Jesus’ death and resurrection, showing that these events were established fundamentals of Christian belief from the beginning. This carefully preserved early confession, combined with Paul’s personal transformation from persecutor to apostle, provides compelling first-generation evidence that Jesus’ followers genuinely believed they had encountered a resurrected Christ.

Other New Testament Writings

Given the diversity of authors, cultural settings, recipients, and genres outside the Gospels and Paul’s writings,6 the rest of the New Testament provides a remarkably consistent witness to Jesus’ death and resurrection. Throughout Acts, the proclamation of the resurrection forms the non-negotiable core of apostolic preaching, with the disciples consistently emphasizing their direct eyewitness testimony that God raised Jesus from the dead (Acts 2:23-24, 32; 3:15; 4:10; 5:30; 10:40; 13:30-37; 17:31). The epistle to the Hebrews describes Jesus as the one who “endured the cross,” “is seated at the right hand of the throne of God” (Hebrews 12:2), and was “brought again from the dead” (Hebrews 13:20). Peter’s epistles speak of the resurrection as the basis of Christian hope (1 Peter 1:3, 21).7 James, the Lord’s brother (named by Paul as a resurrection witness), alludes to “the Lord of glory” (James 2:1)8. John’s first epistle grounds assurance in the present, embodied Son—“that which we have seen with our eyes … and touched with our hands” (1 John 1:1-2); 2 John warns against deceivers who refuse to confess “Jesus Christ coming in the flesh” (v 7); and 3 John praises missionaries who travel “for the sake of the Name” (v 7). Each line assumes that Jesus is not a past ideal but a still-incarnate, bodily risen Lord.9 In Revelation the risen Jesus proclaims, “I died, and behold I am alive forevermore” (Revelation 1:18), a declaration echoed throughout the book, which presents Him as the slain-yet-living One who has conquered death and now reigns forever.10

Taken together, every layer of the New Testament—Gospel narratives, Paul’s letters, sermons in Acts, and later epistles, which were written and circulated within living memory of the events—bears witness to two inseparable events: Jesus’ actual death by crucifixion and His victorious resurrection. These texts were written and circulated within living memory of the events, and they show a consistent testimony of eyewitnesses and early disciples that Jesus truly died and was raised.

Extrabiblical History

The Tomb: Roman Guards and Jewish Customs

Roman and Jewish evidence converges on one point: Jesus’ grave was secured by the strictest human means available in the first century. The empty-tomb claim therefore cannot be brushed aside as the work of grave robbers or scheming disciples.

Roman Guard Discipline: Rotating Quaternions

A standard Roman watch detail was a quaternio of four soldiers.11 Each night was divided into four three-hour vigiliae—two men remained alert while the other two lay directly across the secured point and then swapped places at the horn-signal for the next watch.12 Josephus confirms the same routine for legions in Judea.13 This pattern appears in Acts 12:4, where Peter is assigned “four squads of four soldiers” (tetradioi = four quaternions) so that two could be chained to the prisoner while two stood at the door before rotating. The guards’ motivation for staying awake was absolute: a sentry found sleeping or abandoning post faced summary execution, the dreaded fustuarium (beating to death) or decimation by lot.14 Breaking an official seal also carried capital punishment under Roman law; an imperial edict—the so-called Nazareth Inscription—threatens death for anyone who moves a body or even the blocking stone of a tomb.15 Two soldiers awake, two stretched across the opening, a heavy seal affixed, punishment by death for failure—this tomb guard was the least porous arrangement imaginable. The Gospel polemic that the soldiers were bribed to say they “fell asleep” (Matt 28:11-15) not only logically implies there really was a posted guard; it also highlights how implausible such dereliction would be under threat of death.

A standard Roman watch detail was a quaternio of four soldiers.11 Each night was divided into four three-hour vigiliae—two men remained alert while the other two lay directly across the secured point and then swapped places at the horn-signal for the next watch.12 Josephus confirms the same routine for legions in Judea.13 This pattern appears in Acts 12:4, where Peter is assigned “four squads of four soldiers” (tetradioi = four quaternions) so that two could be chained to the prisoner while two stood at the door before rotating. The guards’ motivation for staying awake was absolute: a sentry found sleeping or abandoning post faced summary execution, the dreaded fustuarium (beating to death) or decimation by lot.14 Breaking an official seal also carried capital punishment under Roman law; an imperial edict—the so-called Nazareth Inscription—threatens death for anyone who moves a body or even the blocking stone of a tomb.15 Two soldiers awake, two stretched across the opening, a heavy seal affixed, punishment by death for failure—this tomb guard was the least porous arrangement imaginable. The Gospel polemic that the soldiers were bribed to say they “fell asleep” (Matt 28:11-15) not only logically implies there really was a posted guard; it also highlights how implausible such dereliction would be under threat of death.

Jewish Burial Customs: Sacred, Sealed Tombs

Jewish burial customs ensured that bodies and tombs were kept secure in a number of ways. First, even in cases involving executed criminals, as Josephus notes, they would “take down and bury” crucified criminals before nightfall in obedience to Deuteronomy 21:22-23.16 Joseph of Arimathea’s request for Jesus’ body fits this norm. Second, the Mishnah, a compilation of oral rabbinical tradition, insisted on the inviolability of tombs. A condemned man’s remains must lie undisturbed for a full year before his bones were gathered to an ossuary.17 Anyone tampering with a grave incurred seven days of corpse-impurity (Numbers 19:11) and severe social stigma. Third, the archaeology of first-century tombs supports this criterion of inviolability. Jerusalem’s rock-cut family tombs used disk-shaped stones—often up to two tons—that rolled down into a groove and wedged shut.18 Mark 16:3 captures the women’s dilemma: “Who will roll away the stone for us?” Without mechanical aid or multiple men, such stones could not be moved quietly—let alone under a Roman guard. Fourth, legal deterrents meant grave robbery was an improbable explanation for an empty tomb. The same Nazareth Inscription that threatens tomb-breakers underscores how grave robbery—especially of a corpse—was considered both sacrilege and treason. Since grave robbers normally sought valuables and not a bloodied body, there was little plausible motive to steal Jesus’ remains.

Why This Matters for the Resurrection Claim

The Romans provided an armed, rotating quaternion under penalty of death; the Jews regarded tomb violation as a serious religious offense; imperial law threatened execution for tampering; a two-ton stone and an official seal completed the security package. As Craig A. Evans notes, “everything humanly possible was done to prevent a resurrection.19 Yet on Sunday morning the stone was rolled back and the tomb was empty—extraordinary circumstances that defy conventional explanations but nonetheless require an explanation! Even critics of Christianity agree that the disciples experienced what they believed were appearances of the risen Jesus and that the tomb story originated in Jerusalem—the easiest place to disprove it by producing a body. These combined Roman and Jewish safeguards mean the simplest explanation for the empty tomb remains the event the early Christians proclaimed: Jesus must have been supernaturally from the dead!

The Romans provided an armed, rotating quaternion under penalty of death; the Jews regarded tomb violation as a serious religious offense; imperial law threatened execution for tampering; a two-ton stone and an official seal completed the security package. As Craig A. Evans notes, “everything humanly possible was done to prevent a resurrection.19 Yet on Sunday morning the stone was rolled back and the tomb was empty—extraordinary circumstances that defy conventional explanations but nonetheless require an explanation! Even critics of Christianity agree that the disciples experienced what they believed were appearances of the risen Jesus and that the tomb story originated in Jerusalem—the easiest place to disprove it by producing a body. These combined Roman and Jewish safeguards mean the simplest explanation for the empty tomb remains the event the early Christians proclaimed: Jesus must have been supernaturally from the dead!

Greco-Roman Sources

Non-Christian Greco-Roman writers offer striking external verification of Jesus’ crucifixion and the earliest Christians’ belief in His resurrection. Tacitus, Rome’s premier historian, records in Annals 15.44 (c. 116 AD) that “Christus, from whom the Christians got their name, suffered the extreme penalty during the reign of Tiberius at the hands of… Pontius Pilatus,” thereby confirming—exactly as the Gospels report—both the crucifixion (“extreme penalty”) and Pilate’s jurisdiction.20 Pliny the Younger, governing Bithynia and writing to Emperor Trajan around 112 AD, notes that Christians met before dawn to “sing a hymn to Christ as to a god,”21 evidence that within about 80 years of the crucifixion believers across the Empire were already worshiping Jesus as divine—difficult to explain if He had remained dead. The Greek satirist Lucian of Samosata (2nd century) mocks but nonetheless corroborates the core facts: “The Christians… worship a man to this day—the distinguished personage who… was crucified on that account… and [they] live after his laws,”22 calling Jesus “the crucified sage” yet acknowledging that His followers regarded Him as more than dead. Written by officials and intellectuals with no stake in promoting Christianity, these secular sources independently attest to Jesus’ execution under Pilate and to the early, widespread conviction that He had conquered death and was therefore considered worthy of worship.

Jewish Sources

Jewish historical sources provide compelling verification of Jesus’ existence, death, and the claims of His resurrection. Flavius Josephus, first-century Jewish historian, mentions Jesus twice in his monumental work “Antiquities of the Jews.” First, in Antiquities 18.3.3, which scholars consider an authentic core of text later embellished by Christian copyists,23 he acknowledges Jesus’ crucifixion under Pilate and references the resurrection claims. Modern scholarly consensus reconstructs Josephus’ authentic testimony as acknowledging Jesus as “a wise man” who “was called the Christ,” was “condemned to the cross” by Pilate, and whose followers reported “he had appeared to them three days after his crucifixion”—language a non-Christian Jew could plausibly have written.24 Josephus’ second, undisputed reference (Antiquities 20.9.1) mentions “James, the brother of Jesus who was called Christ,”25 confirming Jesus’ historical reality and messianic reputation. The Babylonian Talmud, though hostile to Jesus, corroborates His execution: “On the eve of Passover they hanged Yeshu… for he has practiced sorcery and beguiled Israel.”26 This timing aligns precisely with Gospel chronology, and the term “hanged”—Jewish idiom for crucifixion—independently confirms this mode of execution. Jewish writers had every reason to oppose the Christian message, so their grudging acknowledgment of the basic facts about Jesus gives their testimony exceptional historical weight.

Early Church Fathers (Post-New Testament)

The generation of Christian leaders after the apostles also provides early, extrabiblical testimony for Jesus’ death and resurrection. For instance, Clement of Rome (c. 95 AD) refers to the martyrdom of Peter and Paul and then speaks of the hope of resurrection, noting the apostles were “fully assured through the resurrection of our Lord Jesus Christ.”27 This shows that within decades of the events, the Resurrection was a bedrock assurance for the Church. About a decade later, Ignatius of Antioch (c. 107 AD) wrote several letters on his way to execution, in which he repeatedly stresses the reality of Jesus’ death and rising. He warns against those who say Jesus only seemed to suffer, insisting: “He… was truly, under Pontius Pilate… nailed to the cross for us in His flesh… and He truly raised up Himself, not, as unbelievers say, that He only seemed to suffer.”28 Ignatius even recounts that the risen Jesus ate and drank with His disciples in a real body of flesh29—a direct refutation of any docetist claim that the resurrection was just spiritual. This is important: it shows the early church’s unanimous conviction that Jesus physically died and physically rose. By the mid-2nd century, Justin Martyr wrote to defend Christianity, summarizing the gospel story for a skeptical audience. He mentions that after Jesus was crucified, “later, when he rose from the dead and appeared to them, … they believed on him.”30Justin treats the resurrection as a well-known event, prophesied in Scripture and witnessed by many—so much so that he challenges his readers to consider its implications. The early Church fathers, some of whom knew the apostolic generation, unanimously preserve the factual memory of Jesus’ death by crucifixion and His resurrection, confirming that this was not a legendary development but the very basis of the faith from the start.

Mentions in Islamic Tradition

Even Islamic sources indirectly confirm Jesus’ crucifixion. The Qur’an (7th century) addresses it directly: “they [the Jews] said, ‘We killed the Messiah, Jesus son of Mary, the Messenger of Allah’—but they killed him not, nor crucified him, but so it was made to appear to them.”31 This verse (Qur’an 4:157) demonstrates that by Muhammad’s time, Jesus’ crucifixion was so historically established that Islam needed to theologically counter it. Muslim commentators later proposed substitution theories or divine illusions to explain the widespread belief.32 Ironically, these denials serve as evidence that Jesus’ crucifixion was a recognized historical event—one requiring supernatural intervention to dispute—and acknowledge that Christians had proclaimed the resurrection from the beginning.

Modern Scholarship

Modern historical scholarship, ranging from secular academics to believing theologians, has thoroughly investigated the death and resurrection of Jesus. On certain key facts there is broad consensus among experts, while interpretations of the resurrection vary. Here is an overview of what contemporary scholars across the spectrum say about the evidence:

Scholarly Consensus on Jesus’ Death

Jesus’ execution by crucifixion is virtually undisputed among historians. Renowned New Testament scholar John Dominic Crossan, a skeptic and cofounder of the Jesus Seminar, states:33 “That [Jesus] was crucified is as sure as anything historical can ever be.”34 Similarly, atheist New Testament historian Gerd Lüdemann writes, “Jesus’ death as a consequence of crucifixion is indisputable.”35 Even Bart Ehrman, an agnostic historian, calls the crucifixion “one of the most certain facts of history.”36 The reason for this agreement is the convergence of multiple lines of evidence—Christian, Roman, and Jewish—all of which report Jesus’ crucifixion. No serious historian today argues that Jesus somehow escaped death; the fact of His death by crucifixion is considered historically certain.

Scholarly Consensus on Post-Death Experiences

Historians broadly agree that Jesus’ followers genuinely believed he rose from the dead and had experiences they interpreted as encounters with the risen Jesus. E. P. Sanders states, “That Jesus’ followers (and later Paul) had resurrection experiences is, in my judgment, a fact,” adding they “believed this, they lived it, and they died for it.”37 Bart Ehrman similarly notes, “It is a historical fact that some of Jesus’ followers came to believe that he had been raised from the dead soon after his execution.”38 This conviction emerged within days of the crucifixion in Jerusalem itself—timing and location that would be inexplicable unless the disciples were genuinely convinced of Jesus’ resurrection.39 Dale C. Allison Jr. observes: “within a few days of Jesus’ death, some thought he had risen from the dead... within a week of the crucifixion, something... happened which Jesus’ friends took to signal his resurrection.” This near-universal scholarly acknowledgment of the disciples’ sincere experiences constitutes what Gary Habermas terms a “minimum fact” that any historical theory must adequately explain.40

Divergent Interpretations of the Resurrection

When interpreting the Easter morning events, scholarly viewpoints divide. Christian scholars argue that Jesus’ bodily resurrection best explains all evidence. After extensive analysis, N.T. Wright concludes that Christianity’s emergence is inexplicable unless Jesus truly rose: “No other solution to the historical problem” exists to explain both the empty tomb and post-mortem appearances, as “no other bridge will carry the historian across the river.”41 Wright emphasizes that early Christians unanimously proclaimed resurrection—a belief completely counter-cultural for first-century Jews that required an extraordinary catalyst.42 Gary Habermas, who has catalogued resurrection scholarship for decades, notes widespread scholarly agreement on core facts: Jesus’ death, disciples’ experiences, and Paul’s conversion. He reports approximately 75% of scholars accept the empty tomb,43 and virtually all acknowledge Jesus’ followers had genuine experiences convincing them he was alive.44 Habermas and William Lane Craig contend that alternative theories (conspiracy, hallucinations, metaphorical resurrection) fail to coherently explain these facts—hallucinations don’t affect groups simultaneously, and stolen-body theories can’t account for the disciples’ transformation and martyrdom. These scholars present the resurrection as a historical event supported by compelling evidence, asserting that “The evidence for the resurrection is better than for claimed miracles in any other religion.”45

Critical and Alternative Views

Skeptical scholars accept Jesus’ death and the disciples’ sincere belief in resurrection but reject supernatural explanations, often on philosophical grounds. Bart Ehrman acknowledges the disciples’ experiences but argues historians can only conclude the disciples were convinced Jesus was alive, not that God raised him, since the latter is a theological claim. He suggests they likely experienced grief-induced visions, writing, “I don’t know what they saw, but I know they saw something.” Dale C. Allison, after extensive study, admits the mystery of these experiences while rejecting simplistic explanations like hallucination or fraud. The collective nature of early Christian testimony suggests more than isolated hallucinations occurred. Allison candidly confesses, “I am not sure how to account for these experiences in purely natural terms,” yet stops short of affirming a miracle. He observes that resurrection accounts “come to us as phantoms. Most of the reality is gone... Even if history served us much better, there would remain an interpretive gap between what history yields and what the believer longs to know.”46 This highlights historians’ limitation: they can document evidence—Jesus’ death, the empty tomb, followers’ profound experiences—but whether believing or skeptic, the interpretation of the ultimate meaning of the evidence depends on one’s presuppositions and worldview.

Middle Positions

Some scholars adopt intermediate positions. Jesus Seminar members like Marcus Borg described resurrection as spiritual reality—meaningful to disciples without requiring an empty tomb—citing Paul’s reference to a “spiritual” resurrection body (1 Cor 15:44). Critics counter that first-century Jews used “resurrection” (anastasis) exclusively for bodily rising; spiritual exaltation wouldn’t explain the empty tomb or claims of physical encounters. Most contemporary scholars, regardless of theological stance, accept that Jesus’ tomb was found empty shortly after His execution,47 suggesting resurrection faith required both visions and an absent body needing explanation. Alternative theories—disciples visited the wrong tomb, Jesus survived crucifixion (“swoon theory”)—lack academic credibility given Roman crucifixion’s brutality and the certainty of Jesus’ death.48

Modern scholarship broadly agrees on core historical facts: Jesus was crucified and died; his followers soon genuinely believed he was alive and reported encounters with him. Interpretations diverge between Christian scholars (Wright, Habermas) who view resurrection as an actual historical-transcendent event, and skeptics (Ehrman, Crossan) who accept the disciples’ experiences while seeking naturalistic explanations. No serious scholar denies resurrection belief drove Christianity from its inception. As N.T. Wright observes, early Christians didn’t invent resurrection as a concept—it overwhelmed them, and only the combination of empty tomb and appearances could produce their unshakeable conviction that “He is risen indeed.”

Natural Explanations Are Ultimately Implausible

For two millennia, skeptics have proposed natural explanations for Jesus’ resurrection, yet none adequately accounts for all historical facts:

Given these points, most skeptical scholars today do not dismiss the resurrection as mere myth, but rather try to explain the reported facts in some natural way.58 Yet as we’ve seen, each naturalistic theory fails to explain one or more crucial pieces of data. While a miraculous resurrection is certainly extraordinary, it alone accounts for all the evidence in a way no single natural theory can.

Scholarly Consensus on Jesus’ Death

Jesus’ execution by crucifixion is virtually undisputed among historians. Renowned New Testament scholar John Dominic Crossan, a skeptic and cofounder of the Jesus Seminar, states:33 “That [Jesus] was crucified is as sure as anything historical can ever be.”34 Similarly, atheist New Testament historian Gerd Lüdemann writes, “Jesus’ death as a consequence of crucifixion is indisputable.”35 Even Bart Ehrman, an agnostic historian, calls the crucifixion “one of the most certain facts of history.”36 The reason for this agreement is the convergence of multiple lines of evidence—Christian, Roman, and Jewish—all of which report Jesus’ crucifixion. No serious historian today argues that Jesus somehow escaped death; the fact of His death by crucifixion is considered historically certain.

Scholarly Consensus on Post-Death Experiences

Historians broadly agree that Jesus’ followers genuinely believed he rose from the dead and had experiences they interpreted as encounters with the risen Jesus. E. P. Sanders states, “That Jesus’ followers (and later Paul) had resurrection experiences is, in my judgment, a fact,” adding they “believed this, they lived it, and they died for it.”37 Bart Ehrman similarly notes, “It is a historical fact that some of Jesus’ followers came to believe that he had been raised from the dead soon after his execution.”38 This conviction emerged within days of the crucifixion in Jerusalem itself—timing and location that would be inexplicable unless the disciples were genuinely convinced of Jesus’ resurrection.39 Dale C. Allison Jr. observes: “within a few days of Jesus’ death, some thought he had risen from the dead... within a week of the crucifixion, something... happened which Jesus’ friends took to signal his resurrection.” This near-universal scholarly acknowledgment of the disciples’ sincere experiences constitutes what Gary Habermas terms a “minimum fact” that any historical theory must adequately explain.40

Divergent Interpretations of the Resurrection

When interpreting the Easter morning events, scholarly viewpoints divide. Christian scholars argue that Jesus’ bodily resurrection best explains all evidence. After extensive analysis, N.T. Wright concludes that Christianity’s emergence is inexplicable unless Jesus truly rose: “No other solution to the historical problem” exists to explain both the empty tomb and post-mortem appearances, as “no other bridge will carry the historian across the river.”41 Wright emphasizes that early Christians unanimously proclaimed resurrection—a belief completely counter-cultural for first-century Jews that required an extraordinary catalyst.42 Gary Habermas, who has catalogued resurrection scholarship for decades, notes widespread scholarly agreement on core facts: Jesus’ death, disciples’ experiences, and Paul’s conversion. He reports approximately 75% of scholars accept the empty tomb,43 and virtually all acknowledge Jesus’ followers had genuine experiences convincing them he was alive.44 Habermas and William Lane Craig contend that alternative theories (conspiracy, hallucinations, metaphorical resurrection) fail to coherently explain these facts—hallucinations don’t affect groups simultaneously, and stolen-body theories can’t account for the disciples’ transformation and martyrdom. These scholars present the resurrection as a historical event supported by compelling evidence, asserting that “The evidence for the resurrection is better than for claimed miracles in any other religion.”45

Critical and Alternative Views

Skeptical scholars accept Jesus’ death and the disciples’ sincere belief in resurrection but reject supernatural explanations, often on philosophical grounds. Bart Ehrman acknowledges the disciples’ experiences but argues historians can only conclude the disciples were convinced Jesus was alive, not that God raised him, since the latter is a theological claim. He suggests they likely experienced grief-induced visions, writing, “I don’t know what they saw, but I know they saw something.” Dale C. Allison, after extensive study, admits the mystery of these experiences while rejecting simplistic explanations like hallucination or fraud. The collective nature of early Christian testimony suggests more than isolated hallucinations occurred. Allison candidly confesses, “I am not sure how to account for these experiences in purely natural terms,” yet stops short of affirming a miracle. He observes that resurrection accounts “come to us as phantoms. Most of the reality is gone... Even if history served us much better, there would remain an interpretive gap between what history yields and what the believer longs to know.”46 This highlights historians’ limitation: they can document evidence—Jesus’ death, the empty tomb, followers’ profound experiences—but whether believing or skeptic, the interpretation of the ultimate meaning of the evidence depends on one’s presuppositions and worldview.

Middle Positions

Some scholars adopt intermediate positions. Jesus Seminar members like Marcus Borg described resurrection as spiritual reality—meaningful to disciples without requiring an empty tomb—citing Paul’s reference to a “spiritual” resurrection body (1 Cor 15:44). Critics counter that first-century Jews used “resurrection” (anastasis) exclusively for bodily rising; spiritual exaltation wouldn’t explain the empty tomb or claims of physical encounters. Most contemporary scholars, regardless of theological stance, accept that Jesus’ tomb was found empty shortly after His execution,47 suggesting resurrection faith required both visions and an absent body needing explanation. Alternative theories—disciples visited the wrong tomb, Jesus survived crucifixion (“swoon theory”)—lack academic credibility given Roman crucifixion’s brutality and the certainty of Jesus’ death.48

Modern scholarship broadly agrees on core historical facts: Jesus was crucified and died; his followers soon genuinely believed he was alive and reported encounters with him. Interpretations diverge between Christian scholars (Wright, Habermas) who view resurrection as an actual historical-transcendent event, and skeptics (Ehrman, Crossan) who accept the disciples’ experiences while seeking naturalistic explanations. No serious scholar denies resurrection belief drove Christianity from its inception. As N.T. Wright observes, early Christians didn’t invent resurrection as a concept—it overwhelmed them, and only the combination of empty tomb and appearances could produce their unshakeable conviction that “He is risen indeed.”

Natural Explanations Are Ultimately Implausible

For two millennia, skeptics have proposed natural explanations for Jesus’ resurrection, yet none adequately accounts for all historical facts:

“Jesus didn’t really die.” (Swoon Theory)

This suggests Jesus survived crucifixion and later appeared “resurrected.” Medically and historically, this is virtually impossible. Roman executioners were brutally efficient—Jesus’ death by crucifixion is “indisputable”49 and virtually unanimously accepted by historians.50 Even if he somehow survived, a half-dead Jesus would hardly inspire worship; His transformed appearance days later would require an even greater miracle.

“The disciples stole the body.” (Conspiracy Theory)

This earliest Jewish allegation (Matthew 28:11-15) claims the disciples removed Jesus’ corpse to fake a resurrection. This would mean the apostles knowingly built their faith on a lie, then willingly faced imprisonment and martyrdom for this message.51 People may die for beliefs they think true, but it is unlikely all disciples would suffer and die for a known hoax. No conspirator ever confessed, and no body was produced. Even non-Christian writers find it “difficult to maintain that they knew the resurrection to be a hoax” given the apostles’ moral earnestness and sacrifices.52

“They hallucinated or had visions.” (Mass Hallucination Theory)

Could the disciples (and other followers) have sincerely believed they saw Jesus due to grief-induced hallucinations? Psychological experts note that hallucinations are by nature individual events; it would be practically impossible for groups of people to have the exact same hallucination at the same time.53 Yet the records describe Jesus appearing to multiple people together—even to five hundred at once—and doing tangible things like talking, walking, and eating with them.54 Hallucinations also cannot explain the empty tomb, since Jesus’ body would still have been in the grave. As one Christian investigator quipped, if 500 people have the same hallucination, that’s a bigger miracle than the resurrection itself!55 In short, mass hallucination is not a credible explanation for the varied, multi-sensory encounters the early Christians reported.

“The resurrection is a later legend or myth.” (Myth Theory)

This claim suggests the story of Jesus rising from the dead evolved decades or centuries after the fact. But the evidence shows the resurrection proclamation was immediate. The apostle Paul, writing around AD 55, cites an early creed of the Church affirming Jesus’ death, burial, and resurrection appearances.56 This creed is widely dated to within a few years of the crucifixion, indicating that the core resurrection claims go right back to the eyewitness generation. Additionally, the preaching of the resurrection began in Jerusalem just weeks after Jesus’ death.57 If the tomb were not empty or the story were false, critics in Jerusalem would have quickly squashed the movement. Instead, as noted above, we have zero contemporary accounts refuting the empty tomb or the appearances. The timeline is simply too tight for a long myth-making process—the belief was present from the very start.

Given these points, most skeptical scholars today do not dismiss the resurrection as mere myth, but rather try to explain the reported facts in some natural way.58 Yet as we’ve seen, each naturalistic theory fails to explain one or more crucial pieces of data. While a miraculous resurrection is certainly extraordinary, it alone accounts for all the evidence in a way no single natural theory can.

Sociological Evidence

The Disciples’ Radical Transformation and Martyrdom

After Jesus’ crucifixion, His initially fearful followers underwent a dramatic transformation, boldly proclaiming his resurrection even in Jerusalem where he was executed. Historical evidence indicates several disciples were martyred for their testimony (e.g., Peter, Paul, James).59 Their transformation from despair to confident witness, and willingness to suffer death, compellingly demonstrates their sincerity. As historian Michael Licona observes, the disciples “willingly endangered themselves by publicly proclaiming the risen Christ,” indicating they truly believed Jesus appeared to them.60 Even skeptical scholar Gerd Lüdemann admits: “It may be taken as historically certain that Peter and the disciples had experiences after Jesus’ death in which Jesus appeared to them as the risen Christ.”61 The first Christians were utterly convinced Jesus was alive again—a belief for which they voluntarily faced imprisonment and death.62 This sincere conviction, based on personal experience, makes it unlikely they were promoting a known falsehood. People rarely die for what they know is false, and the fact that not one witness recanted—even under threat—strongly suggests they had encountered something extraordinary.

Explosive Growth of the Early Church

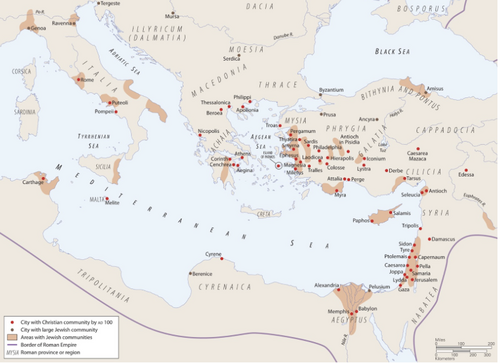

Christianity’s rapid spread to over 60 cities within 75 years of Christ’s death—despite fierce opposition—adds weight to the resurrection claim.

After Jesus’ crucifixion, His initially fearful followers underwent a dramatic transformation, boldly proclaiming his resurrection even in Jerusalem where he was executed. Historical evidence indicates several disciples were martyred for their testimony (e.g., Peter, Paul, James).59 Their transformation from despair to confident witness, and willingness to suffer death, compellingly demonstrates their sincerity. As historian Michael Licona observes, the disciples “willingly endangered themselves by publicly proclaiming the risen Christ,” indicating they truly believed Jesus appeared to them.60 Even skeptical scholar Gerd Lüdemann admits: “It may be taken as historically certain that Peter and the disciples had experiences after Jesus’ death in which Jesus appeared to them as the risen Christ.”61 The first Christians were utterly convinced Jesus was alive again—a belief for which they voluntarily faced imprisonment and death.62 This sincere conviction, based on personal experience, makes it unlikely they were promoting a known falsehood. People rarely die for what they know is false, and the fact that not one witness recanted—even under threat—strongly suggests they had encountered something extraordinary.

Explosive Growth of the Early Church

Christianity’s rapid spread to over 60 cities within 75 years of Christ’s death—despite fierce opposition—adds weight to the resurrection claim.

Distribution of Mediterranean Christianity by AD 10063

From a few dozen followers in AD 30, the movement gained thousands of new believers in Jerusalem mere weeks after the crucifixion by proclaiming the resurrection. Within a generation, Christian communities appeared throughout the Mediterranean world. By AD 112, Roman governor Pliny reported Christianity had so permeated society that pagan temples “had been almost deserted” until official crackdowns began.64 This growth defies sociological expectation: movements centered on crucified leaders typically disintegrated immediately. The resurrection message inspired unshakable commitment, fueled by eyewitness testimony and believers’ own experiences. Significantly, Christianity’s expansion originated in Jerusalem, where Jesus was buried. If His body had remained in the tomb, opponents could have easily disproved resurrection claims by producing His remains.65 That they resorted to persecution instead of displaying His body suggests they had no corpse to expose.66 The Church’s enduring and expanding influence—far exceeding normal outcomes for failed messianic movements67—aligns with believers’ assertion that Jesus truly conquered death.

Not A Culturally Invented Messiah

The disciples would not have invented a dying-and-rising messiah story unless compelled by overwhelming reality. In Second-Temple Judaism, a crucified messiah was utterly counterintuitive—even offensive. Jewish messianic hope envisioned a conquering king who would defeat Israel’s enemies, not a criminal’s execution. As historian Bart Ehrman explains, Jesus’ crucifixion should have proven him a false messiah: it was “the opposite of what would happen with the messiah” in Jewish expectation.68 Similarly, Ehrman notes that no first-century Jew would fabricate a crucified messiah concept because it was so abhorrent.69 Yet early Christians proclaimed Jesus as Messiah after His crucifixion, claiming God vindicated him through resurrection. Only something extraordinary could have forced this dramatic reinterpretation of their beliefs.

Furthermore, the resurrection narrative contains culturally implausible details for an invented story. All four Gospels report women as the first witnesses to Jesus’ empty tomb. In ancient society, women’s testimony was disregarded; Josephus wrote, “Let not the testimony of women be admitted, on account of the levity and boldness of their sex.”70 Fabricators would have made male disciples the primary witnesses for credibility. The inclusion of women as initial witnesses—embarrassing in that culture—strongly suggests truthful reporting.71 The resurrection narrative lacks signs of a crafted legend meant to impress contemporaries; instead, it bears marks of a genuine event that surprised everyone, including the disciples themselves.

The bodily resurrection of Jesus answers the “what changed?” question at the heart of Christian origins: What turned despairing disciples into courageous witnesses overnight? What emboldened them to preach a risen Messiah in a hostile environment? Why did Christianity succeed in taking root, when so many other messianic movements collapsed? The simplest answer is that Jesus’ resurrection was a real event that vindicated His identity and mission, just as the early Christians claimed.

Not A Culturally Invented Messiah

The disciples would not have invented a dying-and-rising messiah story unless compelled by overwhelming reality. In Second-Temple Judaism, a crucified messiah was utterly counterintuitive—even offensive. Jewish messianic hope envisioned a conquering king who would defeat Israel’s enemies, not a criminal’s execution. As historian Bart Ehrman explains, Jesus’ crucifixion should have proven him a false messiah: it was “the opposite of what would happen with the messiah” in Jewish expectation.68 Similarly, Ehrman notes that no first-century Jew would fabricate a crucified messiah concept because it was so abhorrent.69 Yet early Christians proclaimed Jesus as Messiah after His crucifixion, claiming God vindicated him through resurrection. Only something extraordinary could have forced this dramatic reinterpretation of their beliefs.

Furthermore, the resurrection narrative contains culturally implausible details for an invented story. All four Gospels report women as the first witnesses to Jesus’ empty tomb. In ancient society, women’s testimony was disregarded; Josephus wrote, “Let not the testimony of women be admitted, on account of the levity and boldness of their sex.”70 Fabricators would have made male disciples the primary witnesses for credibility. The inclusion of women as initial witnesses—embarrassing in that culture—strongly suggests truthful reporting.71 The resurrection narrative lacks signs of a crafted legend meant to impress contemporaries; instead, it bears marks of a genuine event that surprised everyone, including the disciples themselves.

The bodily resurrection of Jesus answers the “what changed?” question at the heart of Christian origins: What turned despairing disciples into courageous witnesses overnight? What emboldened them to preach a risen Messiah in a hostile environment? Why did Christianity succeed in taking root, when so many other messianic movements collapsed? The simplest answer is that Jesus’ resurrection was a real event that vindicated His identity and mission, just as the early Christians claimed.

Conclusion: The Most Coherent Explanation is Resurrection

In the end, sociological and cultural considerations reinforce the biblical, extrabiblical, and scholarly evidence for Jesus’ resurrection. Notably, even some non-Christian thinkers have found the resurrection hypothesis persuasive. Renowned atheist-turned-deist philosopher Antony Flew acknowledged that “the evidence for the resurrection is better than for claimed miracles in any other religion. It’s outstandingly different in quality and quantity.”72 And Pinchas Lapide, a Jewish historian, declared, “I accept the resurrection of Easter Sunday not as an invention of the community of disciples, but as a historical event.”73 After examining the evidence, Sir Lionel Luckhoo, the world-record-holding defense attorney and former skeptic, concluded: “The evidence for the resurrection of Jesus Christ is so overwhelming that it compels acceptance by proof which leaves absolutely no room for doubt.”74 These testimonies underscore that the resurrection, however improbable it might seem to a skeptic, makes sense of the data in a way that alternative explanations do not.

The resurrection of Jesus is not a blind article of faith against the evidence; rather, it is a belief supported by a convergence of compelling reasons. The historiographical harmony of eyewitness testimony, the guards who secured the tomb with their lives, the Jewish customs and Greco-Roman laws, the disciples’ unshakeable witness, the birth of a movement against all odds, the absence of any credible contrary explanation, and the logic of history all point toward the same astonishing conclusion: Jesus truly died and rose again—an event that changed the course of history and continues to offer hope today!

The resurrection of Jesus is not a blind article of faith against the evidence; rather, it is a belief supported by a convergence of compelling reasons. The historiographical harmony of eyewitness testimony, the guards who secured the tomb with their lives, the Jewish customs and Greco-Roman laws, the disciples’ unshakeable witness, the birth of a movement against all odds, the absence of any credible contrary explanation, and the logic of history all point toward the same astonishing conclusion: Jesus truly died and rose again—an event that changed the course of history and continues to offer hope today!

Some Good Articles & Books

- Geisler, Norman L., and Frank Turek, I Don’t Have Enough Faith to be an Atheist. (Crossway Books, 2004) – See especially chapter 12 (pp. 298-324)—“Did Jesus Really Rise from the Dead?”—for a brief overview of evidence and argumentation. Chapters 9-11 are also helpful regarding the New Testament as reliable documents, eyewitness testimony, and historiography. This is a popular-level, eminently readable, and comprehensive introductory resource from an evidentialist perspective. Except for The Case for the Resurrection of Jesus (Habermas & Licona), of all these “good articles and books,” it is the most comprehensive and accessible in terms of topics covered, whereas the rest are mostly focused on resurrection and aimed at a more scholarly audience.

- Gary R. Habermas, Evidences (Vol 1, 1054 pp), Refutations (Vol 2, 882 pp), Perspectives (Vol 3, available May 2025, 992 pp), & TBA (Vol 4) (B&H Publishing) – Exhaustive magnum opus of the preeminent evangelical scholar of the Resurrection, focuses on his “minimal facts” approach (see below).

- Gary R. Habermas, “The Minimal Facts Approach to the Resurrection of Jesus: The Role of Methodology as a Crucial Component in Establishing Historicity” – Argues for superiority of the approach of establishing the “minimal facts” agreed-upon-by-most—both believers and skeptics—over the traditional and more narrow approach of historically reliable biblical and extrabiblical texts.

- Habermas, Gary R., and Michael R. Licona. The Case for the Resurrection of Jesus (Grand Rapids: Kregel, 2004) – A readable, comprehensive, and user-friendly manual for defending the historicity of the Resurrection.

- Licona, Michael R., The Resurrection of Jesus: A New Historiographical Approach (Downers Grove: IVP Academic, 2010) – Opens with a detailed discussion of historical method and argues that New Testament texts should be weighed with the identical analytical criteria historians use for all ancient sources.

- Wright, N. T., The Resurrection of the Son of God (2003) – Comprehensive 800-page scholarly work arguing for the historical resurrection.

Footnotes

*Footnote Note: You may have to scroll down to find the note you're looking for and you'll definitely have to scroll all the way back up to get back to where you came from. Sorry, but our blog software offers no better solution.

1 Quoted in Richard Lints, The Fabric of Theology: A Prolegomenon to Evangelical Theology, William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 1993, p 265.

2 See (1) Craig S. Keener, Christobiography: Memory, History, and the Reliability of the Gospels, Eerdmans, 2019. Kenner demonstrates that the canonical Gospels fit the genre of first‑century Greco‑Roman biography and are to be assessed by the same historiographical standards applied to other ancient biographies. (2) Michael R. Licona, The Resurrection of Jesus: A New Historiographical Approach, IVP Academic, 2010. Licona opens with a detailed discussion of historical method and argues that New Testament texts should be weighed with the identical analytical criteria historians use for all ancient sources. (3) F. F. Bruce, The New Testament Documents: Are They Reliable?, IVP, 1943; rev. ed. 1981. Bruce’s classic short work compares manuscript evidence, dating, and authorship of the New Testament to other Greco‑Roman literature, concluding that the NT merits the same (or higher) confidence accorded to secular primary sources. Bruce is a trained classicist.

3 See Richard Bauckham, Jesus and the Eyewitnesses, 2nd ed.: The Gospels as Eyewitness Testimony, Eerdmans, 2017. This is a 700-pg tour de force. From the Amazon.com description: It “argues that the four Gospels are closely based on the eyewitness testimony of those who personally knew Jesus. Noted New Testament scholar Richard Bauckham challenges the prevailing assumption that the Jesus accounts circulated as ‘anonymous community traditions,’ asserting instead that they were transmitted in the names of the original eyewitnesses.”

4 (1) Jesus was crucified in Jerusalem during Passover (Matthew 26:2; Mark 14:1; Luke 22:1; John 13:1). (2) He was executed at Golgotha under Pontius Pilate between two others (Matthew 27:33, 38; Mark 15:22‑27; Luke 23:32‑33; John 19:17‑18). (3) Pilate’s officers posted the trilingual charge “King of the Jews” above Him (Matthew 27:37; Mark 15:26; Luke 23:38; John 19:19). (4) Roman soldiers cast lots for His garments (Matthew 27:35; Mark 15:24; Luke 23:34; John 19:23‑24). (5) He was offered sour wine while on the cross (Matthew 27:48; Mark 15:36; Luke 23:36; John 19:29). (6) A group of women, including Mary Magdalene, watched the crucifixion (Matthew 27:55‑56; Mark 15:40‑41; Luke 23:49; John 19:25). (7) Joseph of Arimathea wrapped the body in linen and laid it in a rock‑hewn tomb sealed with a large stone before sunset (Matthew 27:57‑60; Mark 15:42‑46; Luke 23:50‑54; John 19:38‑42). (8) Jesus’ body was wrapped in linen cloths (Matthew 27:59; Mark 15:46; Luke 23:53; John 19:40). (9) The resurrection occurred “on the first day of the week” (Matthew 28:1; Mark 16:2; Luke 24:1; John 20:1). (10) Very early that morning the women found the stone rolled away and the tomb empty (Matthew 28:1‑6; Mark 16:2‑5; Luke 24:1‑3; John 20:1). (11) Angelic messengers announced that Jesus had risen (Matthew 28:5‑7; Mark 16:5‑7; Luke 24:4‑7; John 20:12‑13). (12) The women were the first witnesses of the resurrection (Matthew 28:8‑10; Mark 16:8‑11; Luke 24:8‑10; John 20:14‑18). Including women as eyewitnesses is a fairly radically important detail as their testimony was often disregarded. E.g., see Luke 24:11, lexundria.com, newadvent.com, and sefaria.org. (13) Later that same day Jesus appeared bodily to His disciples (Matthew 28:16‑17; Mark 16:14; Luke 24:36‑43; John 20:19‑23).

5 Paul’s letters date to within one generation of Jesus’ death—Galatians c.AD 48, 1–2 Thessalonians c.50, 1–2 Corinthians and Romans 54‑57—placing them within 2-3 decades after the crucifixion (F. F. Bruce, The New Testament Documents: Are They Reliable? ch 2). Encyclopaedia Britannica likewise notes that the Pauline Letters were “written only about 20–30 years after the crucifixion.” Classical historian A. N. Sherwin‑White observes that Greco‑Roman histories are “generally composed one or two generations after the events, but much more often… two to five centuries later” and concludes that “even two generations are too short a span for myth to supplant the hard historic core.” (Roman Society and Roman Law in the New Testament, pp 186‑189).

6 https://bit.ly/4iBJGkr

7Though not as direct as 1 Peter, 2 Peter assumes the resurrection as the basis for Christ’s exalted status and future return. In 2 Peter 1:16–18, Peter recalls the transfiguration, which anticipates Christ’s resurrection glory, and in 3:4, the expectation of His coming presumes that He has already been raised and reigns. The resurrection, though implicit, undergirds the letter’s eschatological urgency and call to steadfastness.

8 Paul explicitly lists “James” among those to whom the risen Christ “appeared” (1 Corinthians 15:7); the first-century historian Josephus likewise identifies “James, the brother of Jesus who was called Christ” (Antiquities 20.9.1) as a historical figure; and Douglas J. Moo observes that James’s title for Jesus—“the Lord of glory” (James 2:1)—“suggests the heavenly sphere to which He has been exalted and from which He will come” after the resurrection (Moo, Letter of James, comment on 2:1).

9 Matthew D. Jensen, in “Affirming the Resurrection of the Incarnate Christ: A Reading of 1 John” (Tyndale Bulletin 63 (2012): 145-48), argues that 1 John 1:1-4, 4:2 and 5:6-7 are written as resurrection-appearance testimony; Colin G. Kruse (The Letters of John, Pillar NTC, Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2000, 215-16) notes that the present-tense participle in 2 John 7 (“Jesus Christ coming in the flesh”) means “having come and continuing on in bodily existence,” a tacit assertion of Christ’s resurrection; Robert W Yarbrough (1–3 John, BECNT, Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2008, 378 n 7) explains that the missionaries of 3 John 7 travel “on behalf of the Name,” an absolute title that “encompasses the full person and saving work of the now-exalted Jesus.”

10 See Revelation 1:5; 1:17-18; 2:8; 3:21; 5:5-6, 9-10; 12:5; and 13:8.

11 Vegetius, De Re Militari 1.13-14

12 Polybius, Histories 6.37.6

13 Josephus, War 3.87–89

14 Polybius 6.37; Vegetius 2.13Polybius 6.37; Vegetius 2.13

15 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nazareth_Inscription

16 Josephus, Antiquities, 4.202-203

17 Sanh 6:5-6

18 Jodi Magness, Stone and Dung, Oil and Spit, ch. 9

19 Craig A. Evans, Jesus and His World, pp. 148–55

20 https://www.perseus.tufts.edu

21 https://faculty.georgetown.edu

22 https://www.neverthirsty.org

23 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Josephus_on_Jesus

24 https://www.jonathanmorrow.org; https://www.namb.net

25 https://www.blueletterbible.org

26 https://www.blueletterbible.org

27 https://www.earlychristianwritings.com

28 https://www.newadvent.org

29 https://www.newadvent.org

30 https://www.ccel.org

31 https://quran.com

32 https://www.answering-islam.org

33 https://www.gotquestions.org; Re the Jesus Seminar, Birger A. Pearson says, “The Jesus of the Jesus Seminar is a non-Jewish Jesus. … What we have… is an approach driven by an ideology of secularization, and a process of coloring the historical evidence to fit a secular ideal. Thus, in robbing Jesus of his Jewishness, the Jesus Seminar has finally robbed him of his religion. ‘Seek—you’ll find.’ This is one of the “authentic” sayings of Jesus (Matthew 7:7; Luke 11:9; Gospel of Thomas 92:1, colored pink) in [their compilation of, sic.] The Five Gospels. A group of secularized theologians and secular academics went seeking a secular Jesus, and they found him! They think they found him, but, in fact, they created him. Jesus the ‘party animal,’ whose zany wit and caustic humor would enliven an otherwise dull cocktail party—this is the product of the Jesus Seminar’s six years’ research.” (“The Gospel According to the Jesus Seminar”, p 18)

34 https://www.evidenceunseen.com, quoting from John-Dominic Crossan, Jesus: A Revolutionary Biography. Harper One, 1995, 145.

35 https://www.evidenceunseen.com, quoting from Gerd Lüdemann, The Resurrection of Jesus: History, Experience, Theology. Minneapolis: Fortress, 1994, 50.

36 https://www.evidenceunseen.com, quoting from Bart Ehrman, The Historical Jesus: Lecture Transcript and Course Guidebook, Part 2 of 2. Chantilly, VA: The Teaching Company, 2000, 162

37 https://chab123.wordpress.com, quoting from E.P. Sanders, The Historical Figure of Jesus. New York: Penguin Books, 1993, 279-80.

38 https://chab123.wordpress.com

39 https://www.goodreads.com

40 Gary R. Habermas, “The Minimal Facts Approach to the Resurrection of Je- sus: The Role of Methodology as a Crucial Component in Establishing Historicity”. Consider the following 12 such “minimal facts” as quoted in Geisler, Norman L., and Frank Turek. I Don’t Have Enough Faith to Be an Atheist. Crossway Books, 2004, pp. 298–300. In The Risen Jesus and Future Hope, Habermas reports that virtually all scholars from across the ideological spectrum—from ultra-liberals to Bible-thumping conservatives—agree that the following points concerning Jesus and Christianity are actual historical facts: 1. Jesus died by Roman crucifixion. 2. He was buried, most likely in a private tomb. 3. Soon afterwards the disciples were discouraged, bereaved, and despondent, having lost hope. 4. Jesus’ tomb was found empty very soon after his interment. 5. The disciples had experiences that they believed were actual appearances of the risen Jesus. 6. Due to these experiences, the disciples’ lives were thoroughly transformed. They were even willing to die for their belief. 7. The proclamation of the Resurrection took place very early, from the beginning of church history. 8. The disciples’ public testimony and preaching of the Resurrection took place in the city of Jerusalem, where Jesus had been crucified and buried shortly before. 9. The gospel message centered on the preaching of the death and resurrection of Jesus. 10. Sunday was the primary day for gathering and worshiping. 11. James, the brother of Jesus and a skeptic before this time, was converted when he believed he also saw the risen Jesus. 12. Just a few years later, Saul of Tarsus (Paul) became a Christian believer, due to an experience that he also believed was an appearance of the risen Jesus.”

41 https://ntwrightpage.com

42 https://ntwrightpage.com

43 https://www.reasonablefaith.org

44 https://www.reasonablefaith.org

45 https://laurazpowell.org

46 https://www.debunking-christianity.com

47 https://www.reasonablefaith.org

48 https://www.evidenceunseen.com

49 https://wws.crossway.org

50 https://www.crossway.org

51 https://www.crossway.org

52 https://www.crossway.org

53 https://quotefancy.com

54 https://www.crossway.org

55 https://quotefancy.com

56 https://www.crossway.org

57 https://www.crossway.org

58 https://www.crossway.org

59 https://www.crossway.org

60 https://www.biola.edu

61 https://www.crossway.org

62 https://www.crossway.org

63 Tim Dowley and Nick Rowland, Atlas of Christian History, Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 2016, pp 22-24.

64 https://faculty.georgetown.edu

65 https://www.crossway.org

66 https://www.crossway.org

67 For evidence of numerous failed messianic movements in the time of Christ, see (1) Richard A. Horsley & John S. Hanson, Bandits, Prophets, and Messiahs: Popular Movements in the Time of Jesus (Minneapolis: Winston Press, 1985); (2) Craig A. Evans, “Messiahs and Messianic Movements,” in The Encyclopedia of the Historical Jesus, ed. C. A. Evans (New York: Routledge, 2008), pp. 406-409.

68 https://ehrmanblog.org

69 https://www.crossway.org

70 https://www.crossway.org

71 https://www.crossway.org

72 https://www.crossway.org

73 https://www.crossway.org

74 Quoted in his testimony, reprinted at https://www.bethinking.org/did-jesus-rise-from-the-dead/sir-lionel-luckhoo-proves-resurrection.

2 See (1) Craig S. Keener, Christobiography: Memory, History, and the Reliability of the Gospels, Eerdmans, 2019. Kenner demonstrates that the canonical Gospels fit the genre of first‑century Greco‑Roman biography and are to be assessed by the same historiographical standards applied to other ancient biographies. (2) Michael R. Licona, The Resurrection of Jesus: A New Historiographical Approach, IVP Academic, 2010. Licona opens with a detailed discussion of historical method and argues that New Testament texts should be weighed with the identical analytical criteria historians use for all ancient sources. (3) F. F. Bruce, The New Testament Documents: Are They Reliable?, IVP, 1943; rev. ed. 1981. Bruce’s classic short work compares manuscript evidence, dating, and authorship of the New Testament to other Greco‑Roman literature, concluding that the NT merits the same (or higher) confidence accorded to secular primary sources. Bruce is a trained classicist.

3 See Richard Bauckham, Jesus and the Eyewitnesses, 2nd ed.: The Gospels as Eyewitness Testimony, Eerdmans, 2017. This is a 700-pg tour de force. From the Amazon.com description: It “argues that the four Gospels are closely based on the eyewitness testimony of those who personally knew Jesus. Noted New Testament scholar Richard Bauckham challenges the prevailing assumption that the Jesus accounts circulated as ‘anonymous community traditions,’ asserting instead that they were transmitted in the names of the original eyewitnesses.”

4 (1) Jesus was crucified in Jerusalem during Passover (Matthew 26:2; Mark 14:1; Luke 22:1; John 13:1). (2) He was executed at Golgotha under Pontius Pilate between two others (Matthew 27:33, 38; Mark 15:22‑27; Luke 23:32‑33; John 19:17‑18). (3) Pilate’s officers posted the trilingual charge “King of the Jews” above Him (Matthew 27:37; Mark 15:26; Luke 23:38; John 19:19). (4) Roman soldiers cast lots for His garments (Matthew 27:35; Mark 15:24; Luke 23:34; John 19:23‑24). (5) He was offered sour wine while on the cross (Matthew 27:48; Mark 15:36; Luke 23:36; John 19:29). (6) A group of women, including Mary Magdalene, watched the crucifixion (Matthew 27:55‑56; Mark 15:40‑41; Luke 23:49; John 19:25). (7) Joseph of Arimathea wrapped the body in linen and laid it in a rock‑hewn tomb sealed with a large stone before sunset (Matthew 27:57‑60; Mark 15:42‑46; Luke 23:50‑54; John 19:38‑42). (8) Jesus’ body was wrapped in linen cloths (Matthew 27:59; Mark 15:46; Luke 23:53; John 19:40). (9) The resurrection occurred “on the first day of the week” (Matthew 28:1; Mark 16:2; Luke 24:1; John 20:1). (10) Very early that morning the women found the stone rolled away and the tomb empty (Matthew 28:1‑6; Mark 16:2‑5; Luke 24:1‑3; John 20:1). (11) Angelic messengers announced that Jesus had risen (Matthew 28:5‑7; Mark 16:5‑7; Luke 24:4‑7; John 20:12‑13). (12) The women were the first witnesses of the resurrection (Matthew 28:8‑10; Mark 16:8‑11; Luke 24:8‑10; John 20:14‑18). Including women as eyewitnesses is a fairly radically important detail as their testimony was often disregarded. E.g., see Luke 24:11, lexundria.com, newadvent.com, and sefaria.org. (13) Later that same day Jesus appeared bodily to His disciples (Matthew 28:16‑17; Mark 16:14; Luke 24:36‑43; John 20:19‑23).

5 Paul’s letters date to within one generation of Jesus’ death—Galatians c.AD 48, 1–2 Thessalonians c.50, 1–2 Corinthians and Romans 54‑57—placing them within 2-3 decades after the crucifixion (F. F. Bruce, The New Testament Documents: Are They Reliable? ch 2). Encyclopaedia Britannica likewise notes that the Pauline Letters were “written only about 20–30 years after the crucifixion.” Classical historian A. N. Sherwin‑White observes that Greco‑Roman histories are “generally composed one or two generations after the events, but much more often… two to five centuries later” and concludes that “even two generations are too short a span for myth to supplant the hard historic core.” (Roman Society and Roman Law in the New Testament, pp 186‑189).

6 https://bit.ly/4iBJGkr